Digitization on Boards 6: Key Insights

CIOs and CISOs: Managing tensions and working together effectively

A conflict of competing priorities can exist in any reporting structure, but the tension between the priorities of enabling business objectives through technology and maintaining a robust security posture can be especially challenging when it comes to CISOs reporting to CIOs. Many work together effectively and have found a way of balancing tech enablement and security, while some CISOs have said they will never report to a CIO again.

Led by Job Voorhoeve, leader of Amrop's Global Digital Practice, together with Jamey Cummings, Partner at JM Search, we spoke to a number of CIOs and CISOs about their approach to managing these often competing priorities and relationships. They talked about the pros and cons of direct reporting lines, ways of addressing the tensions, and the governance standards needed to ensure that a cybersecurity framework aligns with organizational goals and industry security requirements.

Explore the key insights derived from the study.

The Tensions & Their Causes

Speaking with four CIOs and four CISOs, we analyzed and compared their insights in four areas:

- Root causes and main areas of tension between CIOs and CISOs

- Reporting structure preferences (pros and cons of the CISO reporting to the CIO vs. working as peers)

- Best practices for managing the CIO/CISO relationship

- Best practices for CIOs and CISOs to collectively communicate a unified message about the security program and cyber risks to Boards and ELTs.

Many CIOs and CISOs have demonstrated that they can work together effectively and have found a way of balancing technology enablement and security, however, the tension between the priorities of enabling business objectives through technology and maintaining a robust security posture can often be very challenging. We asked four CIOs and four CISOs to identify the main areas and causes of tension between these two positions.

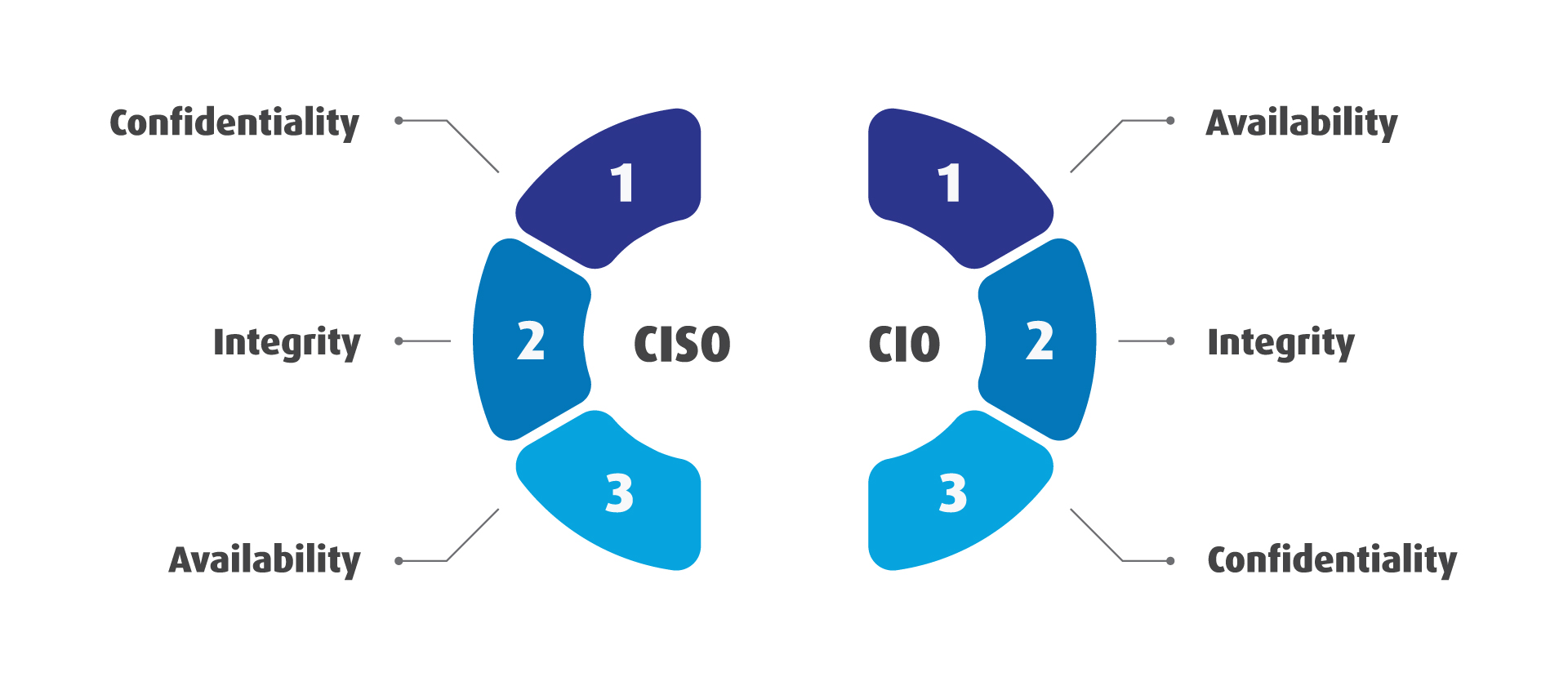

A US-based multi-time CISO, who works for a multi-billion organization in the industrial sector, found it helpful in this context to consider the CIA triad – confidentiality, availability, and integrity, which, according to him, causes natural tension: “From the CISO’s perspective, confidentiality is at the top, integrity is a very close second, and availability, though important, comes third. For the CIO typically availability is the most important factor, integrity – a close second, whereas confidentiality, while not unimportant, becomes the third.”

His experience is echoed in the statement of Felix Voskoboynik, CISO at A.S. Watson Group, which is the largest health and beauty retailer in the world, when he reports that the retail space is growing incredibly fast and you need to be on top of things as an organization – the tension has to do with the speed: “It is a very competitive business, and what we feel and face when it comes to the constraints which exist between IT departments, marketing departments and security, is that the business needs to move at such a fast pace are really challenging to keep up from a security perspective.”

This remains an issue, even as new roles are introduced in the configuration. Harvey Ewing, a CISO turned CIO, who is now a COO at Specialized Security Services, Inc., sees more and more companies move towards a structure which includes CTO, CIO, and CISO. “The CIO and CTO roles are typically predicated on delivery – delivering infrastructure, services, application feature functionalities, and so on, in a timely manner which, I believe, can create a direct tension between these roles,” he says. “This tension is typically due to the CISO being seen as an inhibitor instead of an enabler.”

Jan Joost Bierhoff, the CISO at Heineken, suggests that CISO being seen as an inhibitor creates a kind of false conflict: “The way it’s presented is that the CIO is being hindered by the CISO in some way, and the CISO is always presented as either hindering the CIO’s organization or being ineffectual because they don’t get the support or the buy-in that they need, while actually they’re both working towards the same objective.” At the same time, in Bierhoff’s experience, the CIO’s focus is on building the future of the technology of the company, so they’re a lot more forward-looking. The CISO’s work is more about taking care of keeping “the old house” in shape, where many of the risks are and which could hamper the future. “So, there will sometimes be clashing agendas on priority.”

On the other hand, it is not just the business requirements that create the race and, consecutively, the tension between CISOs and CIOs. According to Martin de Weerdt, CIO at Randstad Global, security too is a very rapidly changing field, since threat actors invent new approaches every day, and trying to stay ahead of them is an ongoing challenge: “There are things that definitely need to be done immediately, while other things might require a bit more time, and the tension can arise when trying to identify them.”

Scott Howitt, currently a CDO at UKG (previously SVP and CIO at McAfee Enterprise, and SVP and CISO at MGM Resorts International) points out that the CISO often has to face a challenge where the CIO gets singularly focused on technology and focused on it for a while: “In the meantime the CISO has to worry about everything, and that can cause internal friction because the CIO has a big deliverable to deliver, while the CISO has many more things to keep track of.”

Emily Heath, a former CISO at Docusign, United Airlines, and AECOM, touches on the possible reason for CIO's often singular focus. “The cloud has changed everything, including the CIO’s role: they’re not creating networks anymore like they used to, so the weight of the CIO’s role has gone heavily into enterprise applications and PC desktop support,” she states. “The CIO traditionally used to have a CISO as head of infrastructure, but now for the most part it’s split out, and the CISO has more relationships to juggle.” Like Ewing, Heath too sees more companies gravitate towards incorporating more roles, like CTO and CDO, in the mix: “I’d say there’s exponentially more headaches between a CISO and a CTO these days than between a CISO and a CIO.”

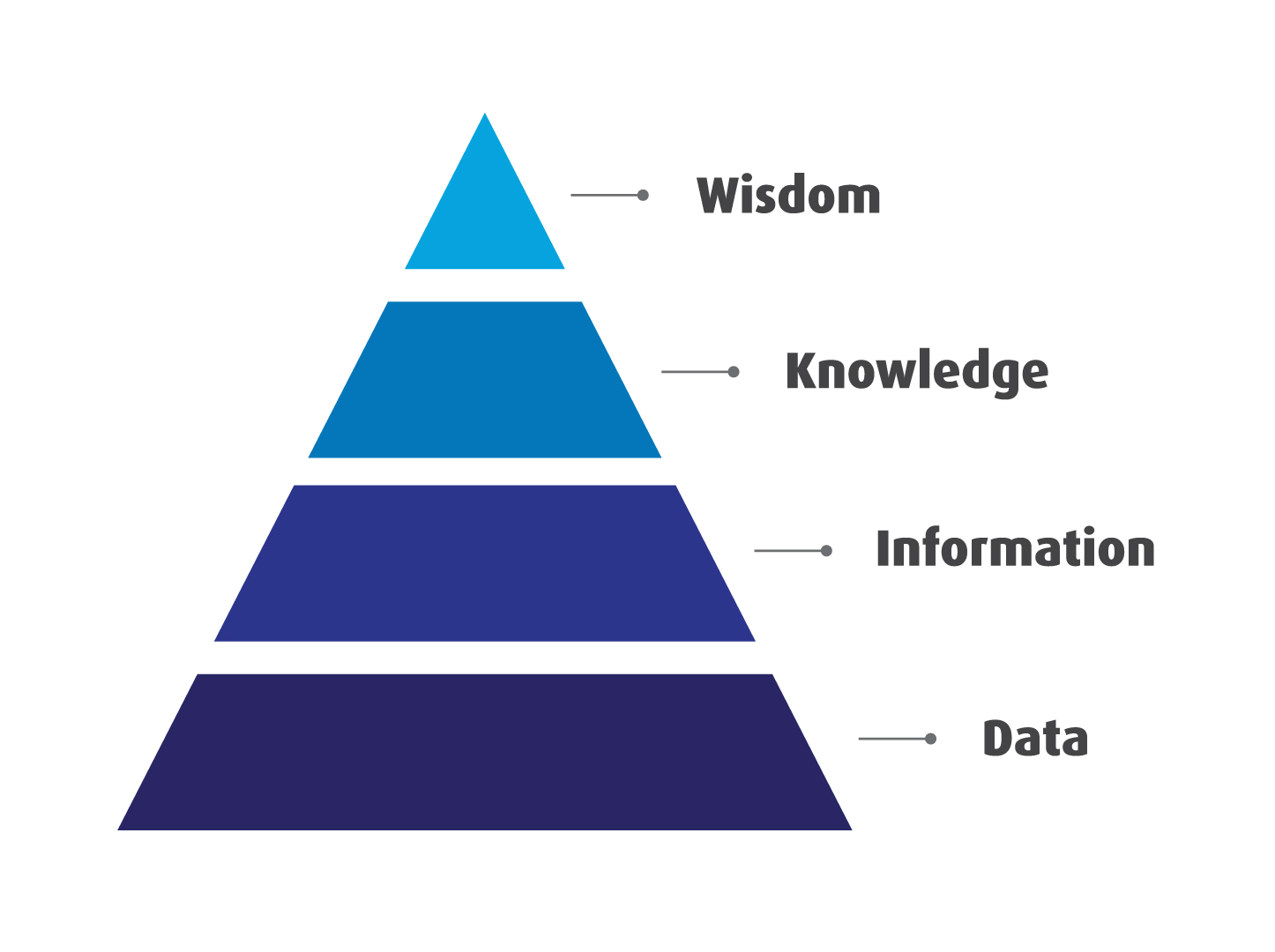

Aloys Kregting, Head of Global Enabling Services at ASML and the former CIO at AkzoNobel, however, sees the main cause of the tension between CIOs and CISOs within the larger relational framework of the organization: “You get this tension when the CIO or the CISO are detached from the rest of the organization, from the stakeholders, and start doing too many things in isolation.” He uses the information pyramid: it shows that IT needs to be aligned with the governance, the organization, the master data, and the business process – the context needs to be made congruent. “To make it concrete: if the CISO is not able to explain how relevant the information security risks are for the business propositions, you will have this friction.”

Reporting Structures

The preferences among our interviewees, when it comes to the reporting structure, unsurprisingly depend very much on their personal experience with regards to what contexts and situations have facilitated or hindered their work and professional development.

A number of interviewees claimed that the reporting structure doesn’t matter too much in itself, but each had particular conditions in mind that need to be in place for successful collaboration, nevertheless. Bierhoff, the CISO at Heineken, said that he doesn’t care much for the reporting structure as long as there’s good communication, besides: “Being within the CIO’s organization has the benefit of working together, not being isolated.” Similarly, de Weerdt, CIO at Randstad, didn’t think the reporting line was important, but thought it was crucial for CISO to have a possibility to “raise alarm if the CIO doesn’t listen, so there’s balance in the relationship”. Based on the specific global structure of their organization, he also notes that “his job as global CIO is to make sure that the local CIO organizations deliver on the things agreed to with the CISO, because they report to him and not to the CISO.”

In Ewing’s experience as CISO turned CIO, a mature enterprise risk mechanism needs to be in place – the tenor needs to be set from the Board and senior executive level. According to him, “the risk needs to be accepted at the right level of the organization, and if it is, the reporting structure doesn't need to become an issue.” Heath, a former CISO and now a Board member, emphasizes the CISO’s responsibility saying that “as a CISO your job is to be a business leader first and a security leader second”, which is why, for 90% of her career she “never really cared about the reporting structure”. In her experience, the reporting structure started to matter at the end of her career: “I wanted to be on public boards and knew that I would get paper-sifted if I hadn't been either part of the C-suite or at least an SVP, so in my last role as a CISO it was important that I reported to the CEO.”

Kregting, SVP Global Enabling Services at ASML and a former CIO, echoes the idea of the CISO needing to be more business-minded, mentioning that they must have good storytelling capabilities, to be able to tell an emotionally engaging story: “A CISO who is outgoing can influence the rest of the company including the CIO. In that case the reporting structure doesn't matter, and then things actually work much better.” In his view, the different scenarios around a functional reporting structure are directly related to people’s characters and insists that good communication is key.

At the other end of the spectrum are CISOs for whom, like for the previously mentioned US-based multi-time CISO, who works for a multi-billion organization in the industrial sector, “shifting the CISO out of the CIO's structure has been a game-changer”. He explained that for him it meant that security was no longer viewed as an internal issue of the CIO’s structure that can get deprioritized. He added, however, that generally more “tension can be observed where there's a lack of investment historically”. Likewise, Voskoboynik, CISO at A.S. Watson Group, sees a lot of conflict of interest when the CISO reports to the CIO, such as budget constraints: “I think that a direct line to the CEO is needed; at the same time, it is important to be connected to the IT organization, to be aligned with business goals.”

Howitt, a CISO turned CIO/CDO, has had different experiences with regards to reporting structure: “If you have a CIO who understands and cares about security, then it can be okay for the CISO to report to the CIO, but often nowadays the CISOs’ security concerns are broader, and CIOs can be singularly focused on technology.” For him there came a time when he said that he as a CISO will no longer work under a CIO, only as peers, so there’s no conflict – and it worked for him. “However, this can create a different kind of conflict, where both are even less involved and aware of what the other is working on,” he admits.

Best Practices: Managing the Relationship

It is often not possible to influence the reporting structure, however, each of the CIOs and CISOs we spoke to has generously shared their best practices for managing a sometimes strained CIO/CISO relationship and ways they’ve attempted to alleviate tension both privately and structurally - on an organizational level.

The US-based multi-time CISO, who works for a multi-billion organization in the industrial sector, invites everyone to focus on the common goals of CIOs and CISOs: “I don’t know of any CISO that says: I’d like to see all the services be unavailable more often, or a CIO who says: I wish I could make things less secure. Everyone has the same objectives; the priority and the waiting shift a bit, but there’s a common ground that can be negotiated. And that’s where I see success as opposed to entrenched positions.” For him, the most important thing he’s always done, is to establish an exception process so that there’s a consistent, informed way to approach and document a risk: “This way, if there really is an operational need that trumps a security need, which happens frequently, we make an informed decision, and move forward. But without that governance approach, without that consistent method of saying: this is how we will deviate from the ideal security state, or, at least, our desired security state, you really end up with a lot more conflicts.”

Both Voskoboynik, CISO at A.S. Watson Group, and Bierhoff, CISO at Heineken, emphasize the educational role of the CISO, the need of the CISO to communicate their concerns clearly, in line with the business goals in order to alleviate the tension. “The CIO won’t be an expert in cybersecurity – they’re going to be missing that education, so it’s crucial to provide it. That way the CIO will better understand the risks and opportunities in the security area and be able to take responsibility for it,” states Voskoboynik. For him it is also about finding a way to make cybersecurity engaging and simple: “I have seen that many tend to complicate things and make it worse than it could actually be. But if you find a way to align with the CIO, to make it more simple, streamlined, and educational for them and for others in the team, if you form the right relationships with your stakeholders, I think that can really simplify things and make them better.” Bierhoff agrees that it’s crucial that the CISO continuously keeps the CIO informed about why he’s concerned about either the CIO’s legacy or his future states: “As a result, in my experience, the CIO will never overlook things which I’m truly concerned about. He might say: “Let’s not do this now, rather next month,” so it’s about balancing priorities.”

Both Ewing, CISO turned CIO, and Heath, a former CISO, emphasize the need for the CISO to be equally focused on security and business needs. According to Ewing, “the CISOs must overcome the traditional stigma associated with their role and must position themselves as strategically aligned to meeting the business’s needs. That doesn’t mean reducing security, but it does mean approaching best practices and all that goes into an effective cybersecurity program through collaboration and communication.” According to Heath, the political capital of CISO in the relationship with CIO (as well as CTO) is highly important. She also offers practical solutions when it comes to CISO’s relationship with engineering teams: ”As a CISO you have to take time with these relationships and bring the engineers in when you’re buying technology. The trust that you build is everything – because the minute they trust you, you’re saving a massive amount of time. What happens then is you slowly start to get out of the way. Eventually you can tell them: you know the methodology – why don’t you operate it yourselves? Now they’re the captain of their own ship!”

The CIOs see communication as key too. Kregting, a former CIO, is convinced that if both the CIO’s and the CISO’s communication skills, drive and capabilities are good enough to come out and show themselves, share the risks and make their story an integral part of the overall picture, then there is no issue: “If the business really understands the information risks for their own environment, there won’t be such tension.” Similarly, de Weerdt, CIO at Randstad, states that there needs to be a very sensible conversation between the CISO and the CIO, as well as the business that eventually needs to pay for everything the CISO and the CIO does – about where we place the priority: “You’re never going to be 100% watertight – it’s impossible, because there are threats arising every day; there will be areas where we need to work hard to keep up and balance risk and investment very thoughtfully, but this is also a way to be as good as we can be.” He also mentions that it’s crucial that the CISO has an opportunity to raise the alarm if the CIO doesn’t want to listen, to make sure there’s balance in that relationship.

Howitt, CISO turned CIO/CDO, sees the advantage in increasing each role’s practical understanding of the other: “I would encourage cross-pollination – the CISO could run security and one middleware for the organization. That would make them a little more cross-functional, and same goes for the CIO – they could run certain aspects of security, especially in the three lines of defense mode. The CIO could run operational security, while the CISO runs governance, security and oversight.”

Best Practices: Unified Messaging

It is not only crucial for the CISOs and CIOs to alleviate the tension and arrive at the best practices in their own collaboration, but to also be able to collectively communicate a unified message about the security program and cyber risks to Boards and ELTs. We’ve asked the interviewees to share what’s worked best in their experience and what the responsibilities of each involved party have been.

Direct Board access for CISOs, regardless of the reporting structure, is stated as a clear necessity by both some of the CISOs and CIOs. The US-based multi-time CISO, who works for a multi-billion organization in the industrial sector, stated: “I’ve had the good fortune throughout my career to always have direct access to the Board – even when I reported to the CIO, we would both be in the room having a conversation together. So, if the Board had a direct question, they could ask me, and they would always get a straight answer. When I used to report to the CIO, I would prepare all my presentation decks, and the data to back it all up, and present that to the CIO. So, if there was any point of conflict, which, again, I’ve typically been lucky not to have, and if something was changed or adjusted, I had at least some auditable record. Today I get to share with everybody beforehand, and everyone’s aware of the metrics, aware of the calculations and wherever the data sources come from, which means everyone has an equal opportunity to control that narrative by taking appropriate action.”

Bierhoff, CISO, who attends the Board meetings along with their CIO, states: “During the meetings with the Board and ELT we do a one-pager, where we show what our current risk profile is, given that the gross risk on the outside world is growing. We show them how our net risk is reduced by the initiatives that we embark on, and that really makes it tangible for them, because they understand that the gross risk is really there – they read newspapers, they talk to their peers, they know that e-commerce sites and B2B apps are going down, factories are being hacked. And we explain what we’re doing to lower that risk, make sure they understand the terminology, and we talk in more detail about the top 5 activities that we’re doing.”

A similar approach is used by de Weerdt, CIO, who attends Board meetings along with the CISO who reports to him. He states: “We have a regular quarterly update, which works very well, because it’s a mixture of what happens in the word in terms of security – it’s basically a refresher about the constant attacks that are happening – and an update about the issues we’ve had. We talk about how we’ve handled those issues, and we mention issues that partners we work with have experienced too. Last but not least, we report against our strategic plan on how we want to improve our security posture in line with the NIST model.”

Voskoboynik emphasizes the CISO’s responsibility in getting a place at the table by proving themselves to their CIO: “The CIO is very likely not going to be an expert in cybersecurity, so, if they have trust in the CISO, if they understand what you’re trying to achieve and if you both have a good working relationship, the CIO will put you in front of the Management.” That’s his situation: he reports to the CIO but interacts directly with the Management team. But it doesn’t end there: “Once you’re there, you need to be able to sell and align, and keep everybody informed in the right way. Because if the CIO would see that you’re somehow in conflict, that you’re reporting about how bad the IT organization is in general, that you’re making them look bad, they’re quickly going to pull you down. So, as CISO you need to develop a way to keep the Management aligned, interested, engaged, and yes, you’re reporting to the CIO because that’s the structure, but they need to also see you as the leader, as someone with the know-how, who will provide them with the right information.”

Both Ewing, CISO turned CIO, and Kregting, a former CIO and now Head of Global Enabling Services at ASML, emphasize the importance of CISO’s communication skills. Kregting suggests that the CIO can be of help to the CISO when it comes to developing these skills: “Some of the CISOs really prefer to work in isolation, doing the brilliant things nobody knows anything about. So, that requires some work, helping them in that journey. As a CIO you can help the CISO by taking the rest of the organization along on the journey, which means different types of communication. For example, one piece of advice I’ve given to CISOs, and which has actually worked quite well, is to use real incidents in their storytelling.”

Ewing states: “What’s really worked for me is translating technology into business language - the Board will want to see and understand exactly what the level of risk is, but they want to see it with regard to its impact on strategic initiatives, top line revenue, EBITDA – they want to understand the business logic and math behind what the CISO is really trying to convey. Early in my career I made the mistake of being too technical to the point where the Board said: look, we love it, you’re a technical guy, that’s great. But what does it really mean for me?” According to him, a Board member providing guidance to the company wants to understand the following: are we driving to the level of risk where I’m comfortable? Have we enumerated those risks? Have you communicated those risks in a business format? Is it going to impact top-line revenue?

- For more information, email us at digital.practice@amrop.com or contact our Digital Practice member in your country!

- Find out more about the JM Search IT, Cybersecurity and Risk Practice here.